The Theory

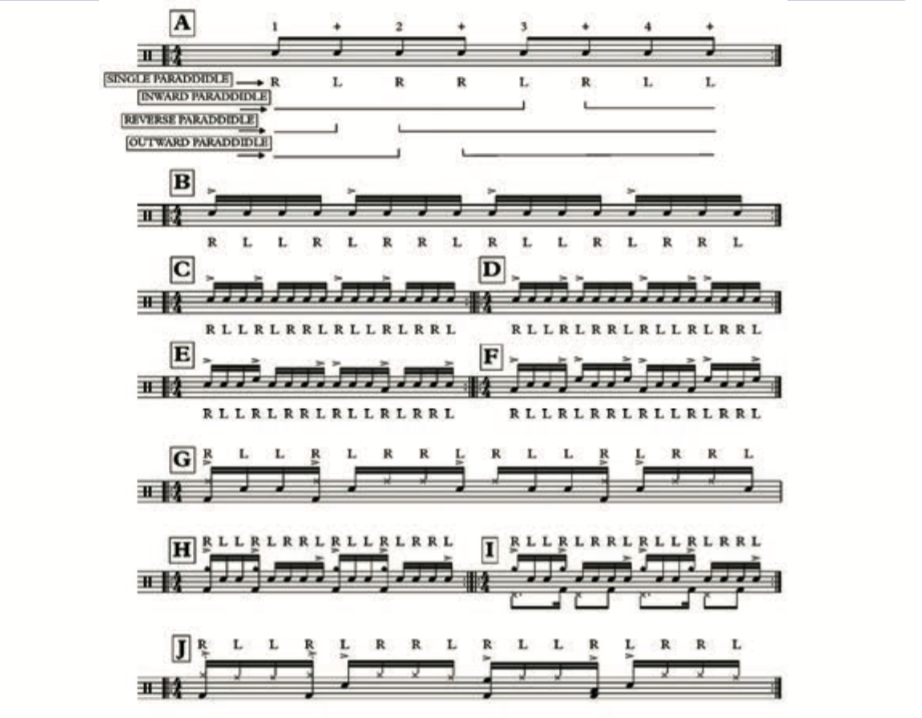

To recap for anyone that’s unsure, the Inward Paradiddle is merely a variation of the regular Single Paradiddle. Our standard paradiddle is RLRR LRLL. If you start on the last right hand stroke of the sticking and continue as normal you get this – RLLR LRRL. This is the Inward Paradiddle, where the ‘diddle’ or the double strokes are in the middle or the inside of the two groups (FIG. A).

The other paradiddles (Outward – RLRL LRLR and Reverse – RRLR LLRL) are also formed in a similar way and can also be applied in similar ways to the variations I’m about to discuss but for the moment, the “inward” is the star of the show..

The Applications

Figure B shows the Inward Paradiddle as 16th notes with accents at the start of each of the groups of four notes. This, in a way sounds no different to the Single Paradiddle so you might as well just use that. However, it’s when you start to move the accents that you can hear how the Inward Paradiddle sounds. Since it’s more difficult to accent on a double stroke I’ve only used accents on the single strokes within the sticking. Figure C is how I’ve learned to feel the Inward Paradiddle in its basic form. The very nature of the sticking puts the second of the single strokes on the offbeat. This automatically creates a very natural groove – even in this basic form. The groove is even more apparent in Figure D where I’ve added the backbeat.

At this point, the simplest application is to place the right hand accents on the floor tom (or right side of the kit) and the left hand accents on the rack tom (left side of the kit). Of course, as with any accent pattern, keep the non-accents soft (ghost notes). Figures E and F show two examples of how this simple application works. This is really the way to approach using the Inward Paradiddle as a fill. You do get that nice groove feel and there are many variations just using this method. You can also play the accents on cymbals in the same way. Just put a bass drum under each cymbal so you don’t end up with too thin a sound.

Grooves!

The fun doesn’t stop here! The next step is to try some grooves. Now, up to this point, regardless of whether you’ve tried accents on toms or as a groove – it’s all pretty much the same vibe as the single paradiddle. The difference for me, and the reason I prefer this paradiddle, is how easily it ts into different styles and situations. I also find that it rolls off the hands a little easier and (for me at least) is easier to instinctively go to on a gig when you’re looking for a fill.

The groove concept is a simple one too. Right hand on hi-hats and left hand on snare drum. Right hand accents get a bass drum too and the snare drum accent is as is. Figure G is notation of my favourite Inward Paradiddle groove. The absence of the back beat on beat two gives the groove a distinct half time groove. The bonus is that you get that super cool 16-note subdivision support behind it that really makes for a great feel.

You can also apply the Inward Paradiddle groove idea in a Latin situation using accents on the cowbell in a somewhat hybrid pattern (FIG. J) and also with a traditional Songo foot pattern if you wish (FIG. I). The idea stems from a modern Latin style called Timba. This Latin groove has more applicable situations than one might think, but nothing is as versatile as the application at Figure J. Every time I go to the ride cymbal on a gig, I find myself using the Inward Paradiddle as a base to help the groove along. You also get some nice articulate bell patterns and this groove; I’ve even used the toms in a perfect combination of both fill and groove applications. So try this for yourself. The better you get at placing accents within the sticking the more natural you’ll be able to use it to improvise it at will and move away from pre-practiced ideas.