“The things you think are important when you come out of school are not what’s really important,” says Jones. “When you start out, you think, ‘Oh, I’m so important! Watch me turn this knob!’ You’re not important. The most important people in the room are the people you’re trying to get performances out of.”

Jones’ event at the 2018 Integrate Expo aims to set graduate audio engineers and music producers straight about the changes brought to an industry where barriers to entry are rapidly vanishing. If anyone can buy a laptop and twiddle the dials themselves, why would they pay you to twiddle for them?

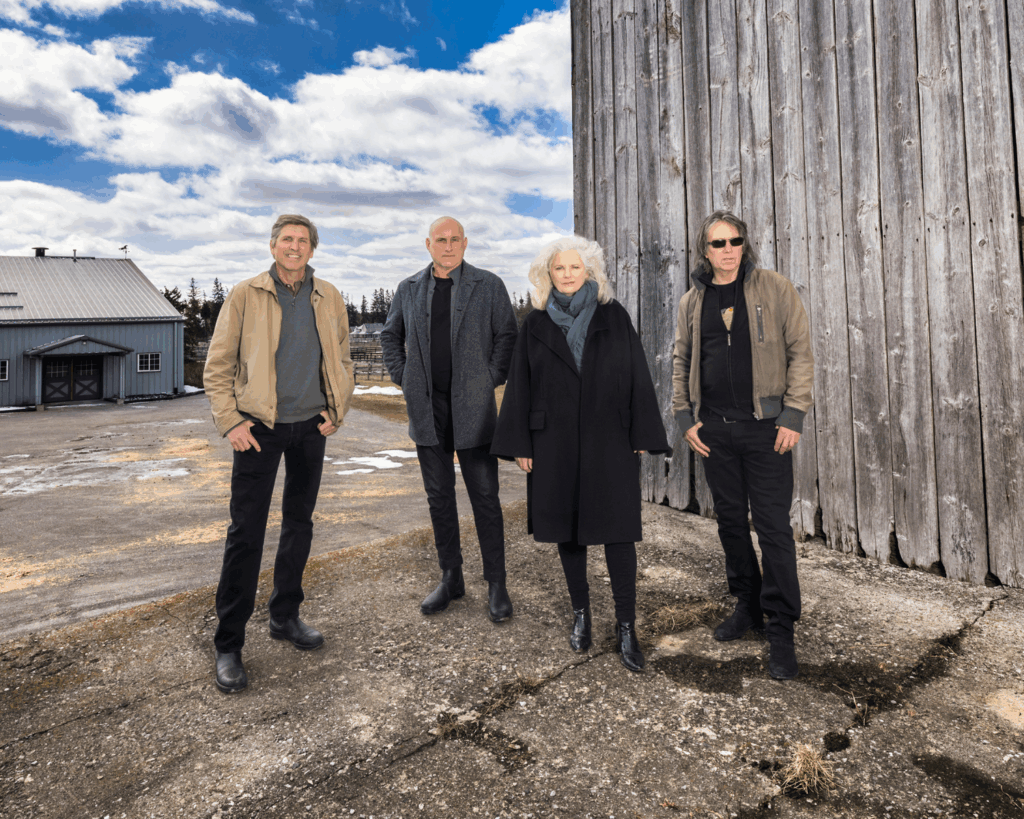

“How do you add value to clients in a world where they can do it themselves?” asks Jones. “I think the most valuable thing you can do is to learn how to get the best out of people and how to make them happy doing what they’re doing. If you’re trying to capture a band on tape, you better learn how to make them play like their lives depend on it.

“When you’ve just finished school, you’re like, ‘Oh, I know how to comp a vocal.’ Well, great. So does 99 percent of everybody else. But what vocal are you comping? Is it a great vocal? Is it a mediocre vocal? That’s the most important thing.”

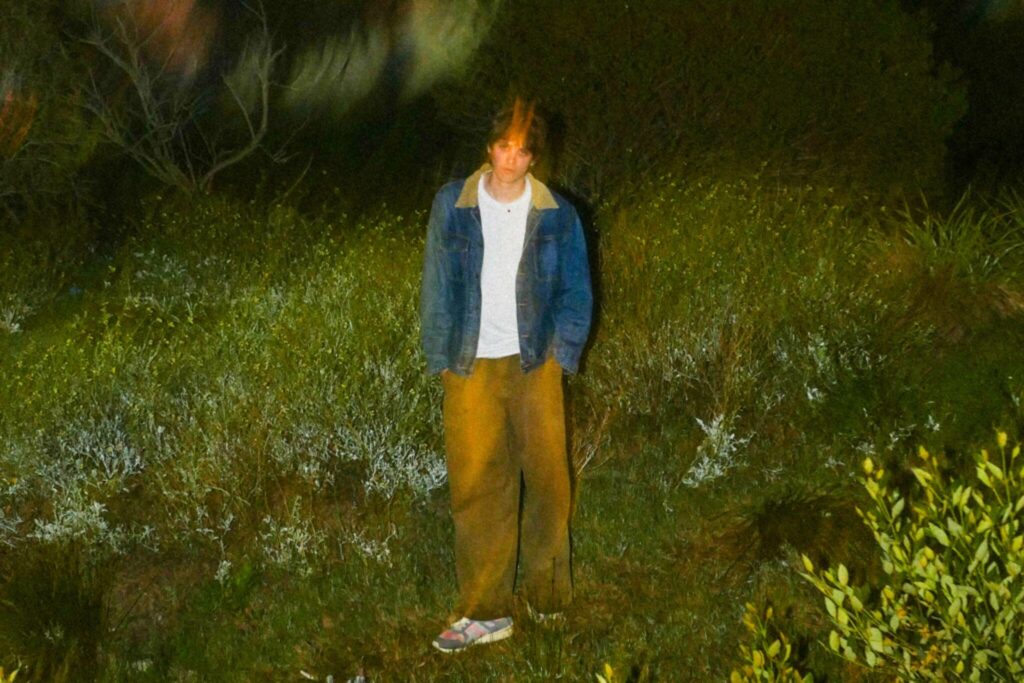

Jones’ love affair with the dial and the fader began when she was 15 and dating a guitarist in a local cover band. After noticing the mixing booth at the back of a venue, Jones was hooked on the idea of becoming an engineer herself, and started pestering the engineers at every gig she went to with questions.

“I understood that there was some process there that made the music go from the band to us—that there was somebody in between,” she says. “I felt an affinity for it.”

The death of the analogue tape was right around the corner when Jones mixed her first record, and she’s been working digitally since the mid-’90s. Jones has watched unsentimentally as big studios have been replaced by smaller studios and home recording setups, and production suites like Pro Tools and Logic have made it possible for anyone with a few hundred dollars in their pocket to become their own producer.

“People can do it themselves. You don’t have to go to a specialised building. You don’t have to hire specialised people, although I have doubts about that. Some people can get away with it, some people can’t.”

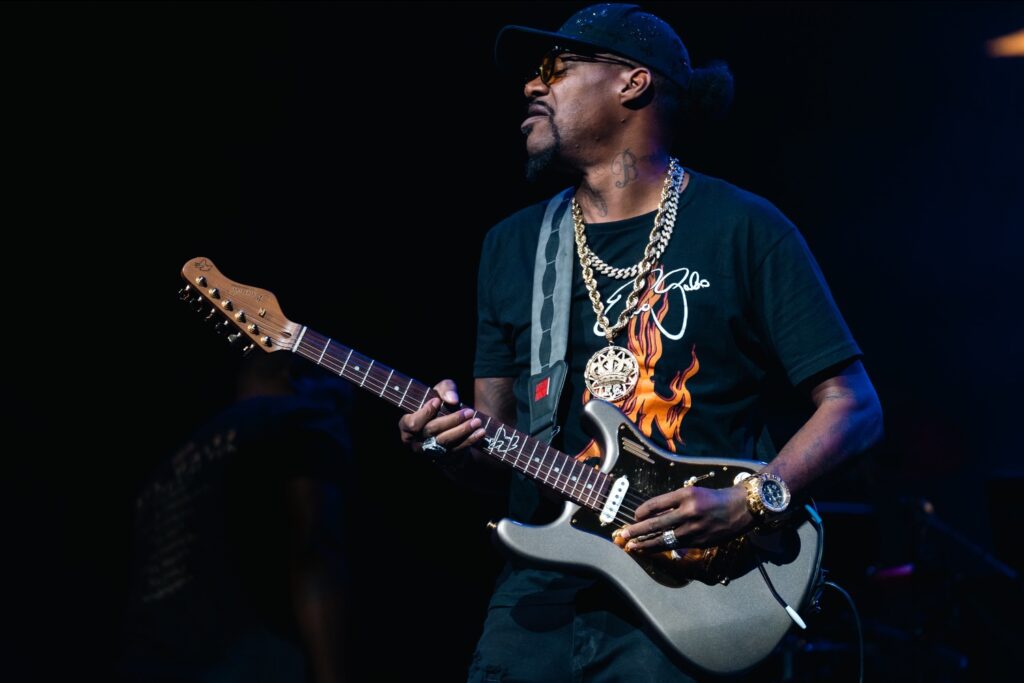

Increasingly sophisticated mixing software has hurt the market value of personal expertise, but in reality, not anyone can just pick up a MacBook and turn out a listenable album. Jones recalls butting heads with one Philadelphia musician who had a little too much faith in the magic of technology.

“He was very talented,” she says. “He wrote great songs, had good melodies. He wanted to produce everything himself, but he did not have the technical knowledge. I spent an awful lot of my time trying to talk him out of various things. He didn’t understand compression properly, didn’t understand distortion, didn’t understand headroom. He didn’t understand a whole bunch of things that separate a professional-sounding record from something you did in your bedroom. The tools are there, but you still have to understand some basic recording concepts to make it sounds like you did it in a big studio.”

The Integrate event will combine interviews from successful freelancers at all levels of the industry—from the big studios to indie record-cuttings done in basements. Jones notes that the levelling of the production process has its advantages and disadvantages. Before the advent of Pro Tools, musicians would have to leave the studio behind for at least a few hours each day, giving them an opportunity to return with fresh eyes. Now, it’s all too easy to take the files home and sit up reworking them until they’ve been skewed beyond all recognition.

“There used to be a bottom, a middle and a top,” she says. “If you weren’t good enough, driven enough or lucky enough to get to the top, there was always a middle and a bottom where you could make a living. The bottom and the middle have now been taken over by prosumer products. People who would have needed to pay you in the past just don’t need to do that anymore… In order to actually have a career, you need to be very good now. Few people are going to make it. That sounds awfully doom-and-gloomy, but it’s true.”

Jones adds that the exploding of the old music hierarchies has also paved the way for new opportunities—for independent creators to make albums without being subject to what a studio estimates will be profitable.

“The really good thing is that, before, you used to have to have vast resources to make music. Now, you don’t. All you need to do is buy a Mac and get Logic and you can do something on par with Hans Zimmer if you’re creatively good enough. There used to be a barrier to entry. In that regard, it’s a great time.”

Catch Paula Jones’s talk on audio engineering at Integrate on Wednesday August 22.